THE recent announcement by Reckitt Benckiser, that they are closing their Harare plant signifies a continuation of the rapid de-industrialisation that threatens to render Zimbabwe a mere trading outpost in the global scheme of things.

The decision by one of the leading fast-moving consumer goods manufacturers in the country, despite denials from management, will eventually have a bearing on the company's overall employment figures and inevitably will dent national output.

In the long run the company will only need to maintain a marketing office, while maybe seconding a logistics company to manage its supply chain.

This development comes only a few years after Unilever also shifted its manufacturing operations from Zimbabwe, leaving only a distribution franchise.

It, therefore, goes without saying that the country's perpetually deteriorating balance of trade deficit, which is now projected to exceed US$3 billion in 2013, after coming in at US$1,6 billion for the four months to April, will come in for further punishment.

Zimra will also have to take it on the chin as formal jobs disappear, further shrinking its already constricted tax base.

While it may be tempting to find solace in conspiracy theories, the reality is the powers that be at Reckitt Benckiser are making a rational business decision, as disconcerting as it may be.

The Zimbabwe operation, from a portfolio perspective of the revenue and earnings, makes little contribution to the global business figures.

This state of affairs has been brought about by the interaction of global trends and practices adopted by global businesses and their intersection with local policy in the affected industries.

Scale matters when the set goal is satisfying global consumer demand. The wave of mass production and globalisation of the consumer has enabled businesses to create a global consumer profile.

Unless Zimbabwe's industry can play catch-up in terms of technology, economies of scale or creating niche products or services, the trend we have been witnessing of de-industrialisation cannot be reversed.

Businesses are no longer producing merely for individual countries, but market segments broken down along geographical lines.

Instead of operating a spattering of production plants across neighbouring countries, global manufacturers are consolidating operations, resulting in fewer plants equipped with production capacities.

This has given rise to global industrial behemoths that enjoy massive economies of scale, resulting in bigger balance sheets, allowing greater marketing budgets, and increased research and development spending.

It is these global trends that have come into contention with our investment and trade policies.

The location of a business entity is affected by many factors, but principally by access or proximity to markets or production inputs often dominating the decision process.

Zimbabwe has a population of 14 million people, a relatively small population. Sixty-five percent of this population lives in the rural areas. Unemployment figures vary from 60% to 80%, meaning income levels are low on a per capita basis.

This translates to the domestic market holding a relatively low appeal in the short to medium-term for global businesses looking for frontier markets in search of growth for their goods and services.

In its favour, Zimbabwe possesses a highly literate population, rich mineral resources, high agricultural potential, decent infrastructure by African standards and central location within the Sadc region.

Our short to medium-term growth path will inevitably be led by our ability to leverage on these advantages and create businesses with the potential to export.

As the tobacco selling season demonstrated, exporting to the rest of the world is the most logical path to economic growth and prosperity, given the size of our domestic market and low per capita investment in research and development.

Broadly speaking, much of our investment and trade policies are in line with developing countries practices, with the notable exception of our indigenisation policies.

The concept of indigenisation, notwithstanding its critics, is a sound proposition. It is in the long-term interest of any country to have local economy “gamed" in favour of locals.

Indeed it is in the long-term interest of even foreign investors for local citizens to dominate economic activities as this promotes long-term stability (assuming that the principle of shared prosperity abides).

China has since the seventies, maintained an iron grip over its economic affairs and only began opening up gradually in economic sectors where they deemed themselves competitive. India has followed a similar path with the first major form of economic liberalisation taking place in the early nineties.

But both of these countries were not even original in their approach in handling foreign direct investment. The US in the late 19th century was the largest importer of foreign capital, circumstances that led it to introduce a number of federal and state laws such as the 1864 National Bank Act that required directors of national banks to be American and the Federal Alien Property Act of 1887, that controlled foreign ownership of land.

These laws arose as a means to counter the threat of foreign capital, (largely British capital) in those days taking over key economic sectors.

Laws such as these were enacted from Independence right up to mid-20th century, when it became arguably the world's pre-eminent economic power.

It was then that its free trade policies became its stock in trade. Much of what we call the first world today followed the same path, with countries like Ireland being the few notable exceptions.

The shortcomings of our indigenisation laws lie at the core definition of indigenisation, the simple standard of prescribing majority control to local Zimbabweans and the instruments deployed to support these objectives.

In its present form, indigenisation amounts to a sledge hammer, as opposed to a scalpel which would reap a richer return and a more efficient outcome.

Our present indigenisation policy framework requires further context both in terms of scope and depth. Continued implementation in its present raw form, will result in a disfigured economic landscape. There will be huge winners and huge losers.

Indigenisation would benefit from a broader definition, where it is as important to own the skill to operate the asset or processes as it is to own the asset or business. Indigenising the skills and technology should form part of our objectives.

Whereas we are explicit about the need for majority control, other countries though not using the same high pitched tenor, implement policies that amount in their total to tilting ownership in their favour.

France uses a combination of state institutions and friendly hands to maintain control in industries of interest. In Germany foreign takeovers are made difficult due to the close industry-bank relationship and strong labour presence in their supervisory boards.

Britain is noted for informal performance requirements in managing foreign investment, while Japan utilises massive cross-shareholding schemes across companies.

Other forms of assistance come in the form of tax legislation geared to favour locally-owned enterprises, grants and subsidised loans employed to support local industries.

The other shortcoming comes in the form of not taking into account the progress made by local businesses in sectors such as insurance, finance and telecommunications.

Prescribing laws in such explicit manner, runs the risk of stigmatising already successful business entities in the same manner affirmative action has for women globally and BEE in South Africa.

A policy to bring back skilled Zimbabweans living abroad back home and offering them opportunities to start and run businesses will increase the likelihood of building businesses that endure and compete on a global level.

Indigenisation legislation is silent on government's role to support Zimbabwean businesses entering foreign markets. Local businesses have historically been poor salesmen of their wares in foreign lands. Government has offered very little support in promoting the probability of success for local exporters and has too often sought to prey on the few success stories.

It is possible to obtain the objective of a radical outcome using pragmatic means.

----------

Msipha is an independent investment advisor. He is a finalist of the Chartered Financial Analyst Programme. Email: msiphak@gmail.com

- businessdigest

Zimbabwe launches new airline

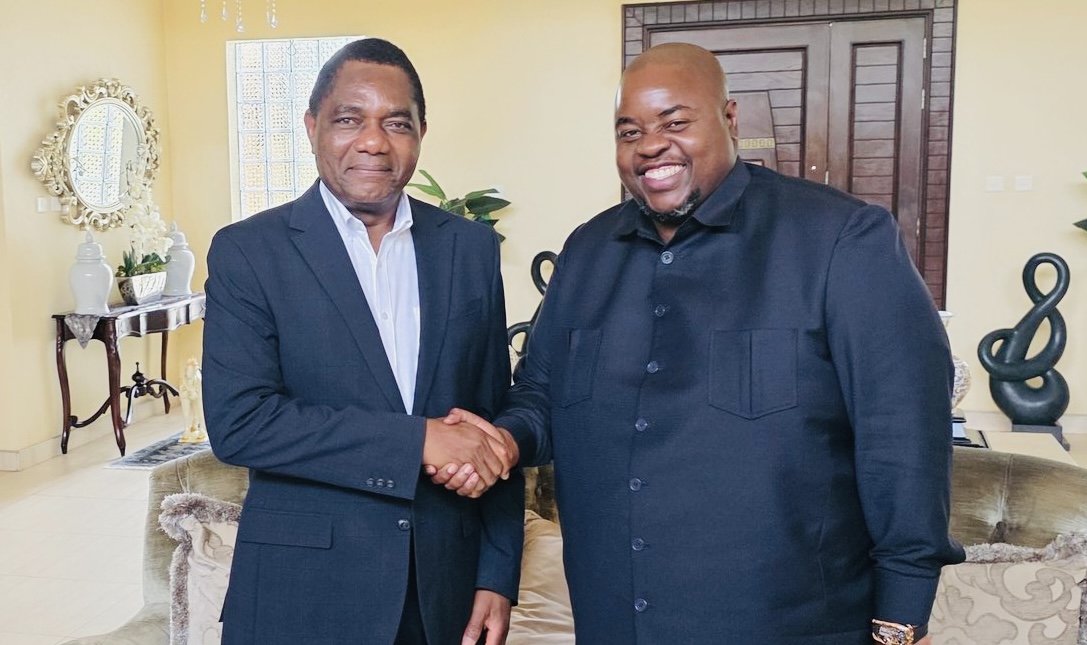

Zimbabwe launches new airline  Hichilema meets Chivayo

Hichilema meets Chivayo  Millions celebrate Diwali festival in India

Millions celebrate Diwali festival in India  SA bitcoin firm mulls Zimbabwe listing

SA bitcoin firm mulls Zimbabwe listing  Gold edges up as traders await guidance

Gold edges up as traders await guidance  Airlink applies for Lanseria to Harare, Bulawayo route

Airlink applies for Lanseria to Harare, Bulawayo route  Young Investment Professional (YIP) Graduate Programme 2019

Young Investment Professional (YIP) Graduate Programme 2019

Young Investment Professional (YIP) Graduate Programme 2019

Young Investment Professional (YIP) Graduate Programme 2019

Editor's Pick