Most of Zimbabwe's leading politicians are lawyers. Nelson Chamisa, Tendai Biti, David Coltart, Job Sikhala, Welshman Ncube, and even President Emmerson Mnangagwa all come from legal backgrounds. The one prominent engineer who often comes to mind in politics is Elias Mudzuri, but even his presence in national debates has been overshadowed by factional squabbles with another lawyer, Douglas Mwonzora.

This dominance of legal minds in Zimbabwean politics is not without consequence. It may help explain why governance in the country relies heavily on statutory instruments - complex legal rules that regulate everyday life - rather than on tangible, large-scale projects that could drive development.

Dan Wang, a Chinese-born Canadian analyst, highlights this contrast vividly in his book Breakneck: China's Quest to Engineer the Future. He argues that China is run by engineers, while the United States is run by lawyers, and that this difference shapes their trajectories. Engineers focus on building - railways, factories, and power plants - while lawyers tend to emphasise processes, legal frameworks, and regulation.

Wang points out that in 2002, all nine members of China's Politburo Standing Committee had engineering backgrounds. This technocratic leadership prioritised construction on a massive scale, giving rise to bullet trains, world-class airports, and advanced manufacturing hubs. Meanwhile, in the US, where law degrees dominate political leadership, projects like California's high-speed rail have been bogged down in lawsuits, environmental reviews, and spiralling costs.

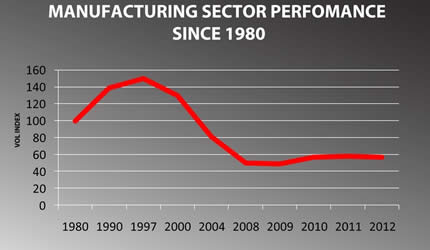

The same parallel resonates in Zimbabwe. Decades after independence, the country still struggles with crumbling infrastructure, power shortages, and stalled mega-projects. Yet, legal battles, constitutional wrangles, and endless political disputes dominate the headlines. Zimbabwean politics often appears trapped in the courtroom rather than the construction site.

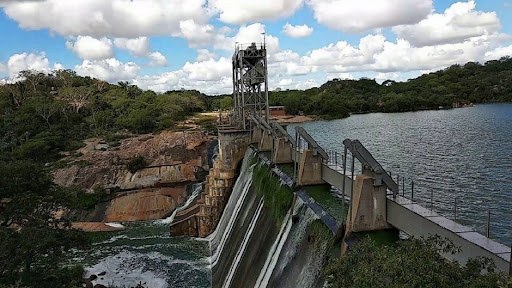

Consider the contrast: China completed its Beijing–Shanghai bullet train in just three years at a cost of $36 billion, carrying more than a billion passengers in its first decade. Meanwhile, in Zimbabwe, flagship projects like the Batoka Gorge hydropower station or the expansion of Hwange Power Station are perpetually delayed, weighed down by financing problems, political disagreements, and governance challenges.

Of course, lawyers play a critical role in defending rights, upholding constitutionalism, and curbing authoritarian excesses. But Wang's thesis raises uncomfortable questions for countries like Zimbabwe: Has the overrepresentation of lawyers in politics tilted the nation towards endless legalism and away from the kind of hard engineering mindset required to rebuild a struggling economy?

China's rise demonstrates the power of an "engineering state" that prizes building over arguing. Zimbabwe, facing an infrastructure deficit and economic stagnation, might need more leaders who think like builders - literally. Until then, it risks remaining a nation of statutory instruments and policy pronouncements, without the highways, factories, and power grids to match.

- DB

David Coltart takes on the Church of England

David Coltart takes on the Church of England  South Africa ripe for a coup

South Africa ripe for a coup  India dumps US Treasury bills

India dumps US Treasury bills  Zimbabwe's dollar stock exchange surges 45%

Zimbabwe's dollar stock exchange surges 45%  Gold edges up as traders await guidance

Gold edges up as traders await guidance  fastjet introduces Bulawayo-Victoria Falls flights

fastjet introduces Bulawayo-Victoria Falls flights  Young Investment Professional (YIP) Graduate Programme 2019

Young Investment Professional (YIP) Graduate Programme 2019

Young Investment Professional (YIP) Graduate Programme 2019

Young Investment Professional (YIP) Graduate Programme 2019

Editor's Pick