WHEN ZANU PF's National People's Conference convenes in Mutare this October, the usual rhetoric of unity, loyalty, and economic recovery will fill the air.

Delegates will arrive from all ten provinces draped in party regalia, singing liberation war songs and chanting slogans that glorify President Emmerson Mnangagwa's leadership.

Yet behind the optics of solidarity, the gathering will serve as an inflection point in the most consequential internal power struggle since the 2017 military-assisted ouster of Robert Mugabe.

This year's conference has been carefully choreographed to project Mnangagwa's unassailable dominance, but the choreography is beginning to fray.

Factional tensions that have simmered quietly for the past two years are now boiling over, pitting Vice-President Constantino Chiwenga – the retired general who helped install Mnangagwa in 2017 – against business magnate Kudakwashe Tagwirei, Mnangagwa's billionaire ally and alleged financier.

The struggle between these two men, and the rival power blocs they represent, could ultimately determine not only who rules Zimbabwe after 2028 but whether ZANU PF can survive the transition intact.

At the heart of the unfolding drama lies the "ED2030" campaign, a push by Mnangagwa's loyalists to amend the Constitution and extend his presidency beyond the current two-term limit, which expires in 2028. The campaign, which began as a social media slogan, has now evolved into a formal political project. Provincial party structures in Mnangagwa's strongholds – notably Midlands and Mashonaland West – have already passed resolutions endorsing him to "lead until 2030." The party's Legal Affairs Department, led by Patrick Chinamasa and Justice Minister Ziyambi Ziyambi, has been tasked with exploring the legal mechanics of making that happen.

Officially, Mnangagwa has neither endorsed nor rejected the campaign. Unofficially, his closest allies have been aggressively promoting it, framing it as a continuation of "Vision 2030," the government's development blueprint. The Mutare conference will be the critical test: can the president translate this wave of provincial endorsements into a national consensus within ZANU PF? Or will the push for a constitutional amendment expose dangerous divisions within the party's top ranks?

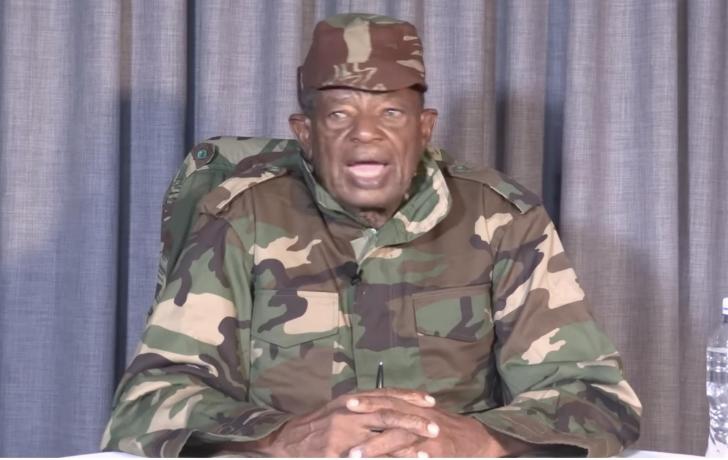

Constantino Chiwenga's unease with the ED2030 project is no secret. Once Mnangagwa's indispensable ally, he has increasingly positioned himself as the custodian of the Constitution and the party's founding ethos. Insiders say the retired general believes the president should honour the two-term limit and facilitate an orderly succession process – one that, ideally, would see Chiwenga himself take over.

Chiwenga's resistance is not merely personal ambition cloaked in principle. It reflects a deeper frustration within sections of the military and liberation war veterans who feel marginalised by the growing influence of business elites in party politics. Many of these figures – particularly from Mashonaland East, Manicaland, and Masvingo – remain loyal to Chiwenga and view him as the guarantor of their historic role within the liberation movement.

His rhetoric in recent months has been strikingly defiant. Without naming names, he has repeatedly warned against "money changers and briefcase politicians" corrupting the party from within.

Those close to him say these remarks are aimed squarely at Kudakwashe Tagwirei, the businessman widely seen as Mnangagwa's financial backbone and chief patron of the ED2030 campaign.

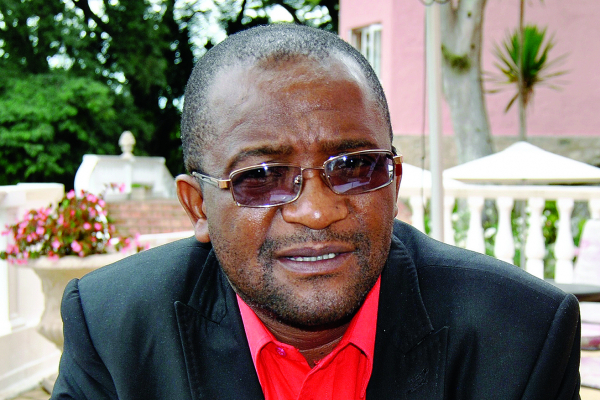

Tagwirei's ascent from businessman to political power player has been meteoric and controversial. Once lauded for financing government programmes through his Sakunda Holdings conglomerate, Tagwirei has since become synonymous with "state capture" in the eyes of many Zimbabweans. He is believed to bankroll ZANU PF's campaigns, sponsor select politicians, and maintain influence over strategic sectors such as fuel, mining, and banking.

His growing political ambitions have alarmed traditionalists within ZANU PF.

His attempt to be appointed to the party's Central Committee earlier this year was reportedly blocked after Chiwenga intervened, only for him to be co-opted in August.

The fallout was public and bitter: party spokesperson Christopher Mutsvangwa accused Tagwirei of trying to "buy his way into politics," while the businessman shot back, insisting his philanthropy was being misrepresented.

For Chiwenga and his allies, Tagwirei symbolises everything that has gone wrong in the party since 2017 – the rise of a comprador bourgeoisie that uses money to manipulate the levers of political power.

To Mnangagwa's camp, however, Tagwirei is indispensable: a loyal financier whose resources have kept both the party and government afloat amid sanctions and economic turbulence.

This tension – between revolutionary legitimacy and financial pragmatism – is now at the centre of ZANU PF's identity crisis.

Mnangagwa, for his part, faces an increasingly delicate balancing act. He owes his initial ascendancy to the military and to Chiwenga's intervention in 2017, but his political survival since then has depended on cultivating an alternative power base rooted in business, provincial patronage, and younger technocrats.

Tagwirei has been central to this strategy, providing not only financial muscle but also the infrastructure of political loyalty.

Yet Mnangagwa is acutely aware that pushing the ED2030 agenda too aggressively could provoke a backlash from the very forces that installed him. The president's public posture, occasionally downplaying talk of a term extension while allowing his allies to champion it, reflects this strategic ambivalence. Mutare will test whether he can maintain this balancing act without alienating either camp.

The parallels with the run-up to the 2017 coup are impossible to ignore. Then, as now, an ageing president sought to manipulate succession in his favour.

Then, as now, competing factions mobilised around different sources of power – o e military and institutional, the other civilian and economic. The Mugabe–Grace–G40 triangle has been replaced by the Mnangagwa–Tagwirei–Chiwenga triad, but the underlying logic remains: factional competition within ZANU PF tends to escalate when the presidency becomes personal rather than institutional.

The crucial difference this time is that the players understand the cost of open conflict. The 2017 intervention destabilised Zimbabwe's economy, fractured regional alliances, and left enduring scars within the military.

Both Mnangagwa and Chiwenga know that a repeat would risk total collapse – yet history suggests that when party mechanisms fail to mediate succession, coercive solutions become thinkable.

Three plausible scenarios emerge from the Mutare conference. Scenario one: The ED2030 triumph – in which Mnangagwa's allies succeed in pushing through a conference resolution endorsing an extension of his presidency.

The decision is wrapped in populist rhetoric about "completing Vision 2030," and any dissenting voices are drowned out by a chorus of praise.

Tagwirei's financial influence ensures logistical dominance – from transport to delegates' allowances - while Chiwenga is left isolated but publicly compliant.

The immediate result would be unity on paper, but behind the scenes, the security establishment could begin recalibrating its loyalties, quietly preparing for the post-Mnangagwa era.

Scenario two could see Chiwenga, leveraging his provincial support and military networks, blocking an outright endorsement of ED2030.

The conference produces a face-saving compromise: praise for Mnangagwa's leadership but no commitment to amend the Constitution.

This scenario preserves temporary cohesion but defers the crisis, setting the stage for a bruising showdown at the 2027 elective congress.

The final scenario – if the ED2030 campaign is forced through aggressively, and if Tagwirei's political ambitions become too overt, Chiwenga's allies could mount an open rebellion.

This could take the form of public dissent by war veterans, strategic resignations, or coordinated pushback from provincial structures.

Such a rupture would risk plunging ZANU PF into its deepest crisis since independence – a civil war within the party, fought not over ideology but over power, wealth, and survival.

The stakes of this power struggle extend far beyond party politics.

For ordinary Zimbabweans, another bout of elite infighting could derail any hope of economic stabilisation or international re-engagement. Investors, already wary of policy volatility, will interpret internal discord as further evidence of institutional fragility. Regionally, a destabilised Zimbabwe would unsettle the Southern African Development Community (SADC), forcing neighbours to confront a renewed political crisis in Harare.

For ZANU PF itself, the danger is existential.

The liberation movement has survived for four decades by projecting an image of disciplined unity, even in the face of intense internal rivalry. But the fusion of business interests and political patronage – embodied by the Tagwirei factor – threatens to erode that cohesion irreversibly. If the party becomes little more than an arena for competing oligarchs, it may lose the revolutionary mystique that has anchored its legitimacy since 1980.

The Mutare conference will therefore not just decide the future of Mnangagwa, Chiwenga, or Tagwirei.

It will reflect the moral and institutional trajectory of ZANU PF itself.

The choice facing the ruling elite is stark: to reassert constitutionalism and collective leadership, or to plunge deeper into the politics of personal rule and plutocratic patronage.

If Mnangagwa uses Mutare to consolidate power through legal manipulation and financial leverage, he may win the battle but lose the war, for every such victory accelerates the party's internal decay.

If Chiwenga and the traditionalists manage to restrain this drift, they may temporarily restore balance but risk unleashing forces they cannot fully control.

One way or another, Mutare 2025 will be remembered as a defining moment – a mirror held up to the ruling party's soul. Whether it reflects renewal or ruin will depend on whether ZANU PF's leaders choose the hard discipline of principle over the seductive comfort of power.

- Gabriel Manyati

Chiwenga's ally mobilises protests to oust Mnangagwa

Chiwenga's ally mobilises protests to oust Mnangagwa  Starlink plans to go big in South Africa

Starlink plans to go big in South Africa  'Some very strange things are happening in China!'

'Some very strange things are happening in China!'  Zimbabwe's dollar stock exchange surges 45%

Zimbabwe's dollar stock exchange surges 45%  Gold edges up as traders await guidance

Gold edges up as traders await guidance  Gold shatters $4,000 milestone

Gold shatters $4,000 milestone  Young Investment Professional (YIP) Graduate Programme 2019

Young Investment Professional (YIP) Graduate Programme 2019

Young Investment Professional (YIP) Graduate Programme 2019

Young Investment Professional (YIP) Graduate Programme 2019

Editor's Pick